A major preoccupation of academics is finding and

filling a “gap in the literature.” These “gaps” can be quite elusive and

difficult to find but, so we’re told, finding them and filling them is an

important contribution to our field/s of study, and to academia in general. Especially

as graduate students, we are told to make sure we write about something that

hasn’t been written about before, or do something that hasn’t been done before,

if we want to make a splash and have ourselves and our work be noticed by the

Big Fish in academia.

And yet—in the

same breath—we are cautioned to not do something too wild or too unfamiliar.

Afterall, ‘who do we think we are?’ We have to make sure we simultaneously

secure our work comfortably in the protective arms of a successful academic’s

theories and ideas while saying something new.

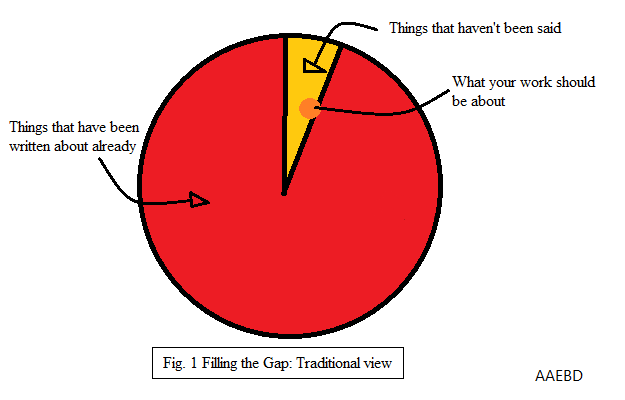

I imagine this balancing act to be something like this:

But, a pretty important question that should be

asked is why it matters to follow this model of scholarship. What is worthwhile

about it? Of course, we can’t sustain a model of academia in which no one

contributes (in the broadest possible sense of the word) anything new to the

existing bodies of work, but why is it that so much emphasis has been placed on

finding and filling a content gap?

In some fields this makes sense: i.e. in Medicine: “Thus

far, people have found cures/ effective treatments for laryngitis, smallpox,

and polio, but no one has yet found a cure/effective treatment for

tuberculosis; my research seeks to find that.” You can imagine Robert Koch, the German physician and

scientist who in 1882 discovered the bacteria that causes tuberculosis,

proposing something like this in a thesis proposal or grant application.

Alright, it seems legitimate. Good job and finding and filling a content gap,

Dr. Koch!

|

| Dr. Robert Koch keeping it cool; yanked from Wikipedia Images |

But this same model

of academia is slightly less straightforward in other disciplines. I feel I

have a right to pick on anthropology of religion because that is my own field.

I wrote my master’s thesis on Protestant Charismatic Christian practices of

spiritual healing in a Canadian (Ottawa, to be specific) context. It was a

small-scale ethnographic study that drew from a tiny sample. In justifying its

validity as a research topic, I argued something like this: “there are studies

of spiritual healing in non-Western countries, and in non-Christian religions,

okay and there’s also one of a Catholic Charismatic Christian community in the

USA…but no one has written about the phenomenon in a Canadian, Protestant

context! I’ll write about that!”

Gap = found and filled.

Gap = found and filled.

…But to what end? And for what point?

Don’t get me wrong. I think there’s value in studying a variety of topics, even the ones that don’t contribute to the cure of tuberculosis. As a cultural anthropologist, I believe that learning more about the diversity of human thought and behaviour (both past and present) is extremely valuable. And as an (aspiring) advocate and activist, I think it’s important to bring underrepresented and marginalised experiences/stories/voices into broader conversations—to know that not everyone thinks/believes the same things we do, and that even within a religious community like “Canadian Protestants” there’s a lot of diversity of beliefs. Being reminded of these beliefs and learning more about the details of them can, I think, help us to reduce prejudice and hatred for people who believe/think/act differently than we do. This hope is a significant motivating factor behind my scholarly pursuits.

But, realistically, did my writing an academic dissertation about this accomplish the very thing that motivated me to write it? Let’s see.

□ Learn about the diversity of human thought and behaviour?

Check.

□ Bring underrepresented and marginalised experiences into broader [scholarly] conversations?

Check.

□ Help reduce people’s prejudice and hatred for people who believe/think/act differently.

....I’m personally not so sure about that last one, and here’s why:

Let’s consider my master’s thesis, which I successfully defended in June 2015.

Even though I wrote its opening pages in a narrative voice that read like fiction, and even though I tried to keep academic jargon to a minimum throughout it, at ~60,000 words and tonnes of footnotes and references, it isn’t exactly a cake-walk. And, because of the expectations of academic theses, I had to include a full-scale literature review and methods/theory section, both of which can be quite boring to read through for a specialist in your field, let alone someone outside of that.

Although it’s by no

means a hard and fast rule, there is a tendency within specialised academic

writing to spiral deeper and deeper into a hole of intimidating jargon and confusing

ideas, wherein what once started off as interesting and intelligent transforms

into a boring beast.

Or, as one of my professors at the University of Ottawa used to say: “you know that story where that guy can turn whatever he wants into gold? So theoretically you could take a big shit and then turn it into gold? Well academics already have the gold, but they somehow have found a way to make everything they touch turn to shit.”

Here’s how I sometimes picture this going.

Or, as one of my professors at the University of Ottawa used to say: “you know that story where that guy can turn whatever he wants into gold? So theoretically you could take a big shit and then turn it into gold? Well academics already have the gold, but they somehow have found a way to make everything they touch turn to shit.”

Here’s how I sometimes picture this going.

(Okay, so I’m being a bit facetious and don’t really think this graph is always true, but you get my point.)

I wonder if all the

thought and time I put into my thesis topic would have been better served if I

had done something else with the material. Something other than an academic

dissertation. Because, really, who even read the thing? My supervisor, bless

her soul, read my full thesis--and more than once! My two evaluators read it. My graduate

director read it and, in a surprising turn of events, the secretary of my

faculty read it. It’s on academia.edu and other similar academic sites, and some colleagues have downloaded it

and probably read bits and pieces of it. Although I gave a copy of it to all of

my research participants, most of them admitted to only skimming the first few

pages before deciding to just read the two-page summary that I wrote especially

for them. So, other than my adoring parents, I wonder if it has been read by anyone

outside of the academy. I would guess not...which feels like a shame, because I think that (at

least some of!) the ideas within it have potential to promote positive change. (Also, the federal government funded my studies, which is a whole other thing to consider..!)

I think academics

need to focus on finding and filling a different gap. Not simply a

content-based gap, but the more general gap between ivory tower thoughts and

the world outside of the ivory tower. Some people advocate for leaving academia's Ivory Tower and this blog has some interesting posts on that if you want to check the out! And this blog tries to demystify the Ivory Tower and reclaim the term in a positive sense.

And yet, academia has arguably retained some pretty smart minds (you can debate me on this if you want); and a significant part of an academic’s job is literally to think, to learn, and to teach. This is an amazing privilege for each individual, and it could be a great contribution to others—both inside and outside of academia. But a lot of this potential is lost if only other academics are affected by (or included in) academic pursuits.

And yet, academia has arguably retained some pretty smart minds (you can debate me on this if you want); and a significant part of an academic’s job is literally to think, to learn, and to teach. This is an amazing privilege for each individual, and it could be a great contribution to others—both inside and outside of academia. But a lot of this potential is lost if only other academics are affected by (or included in) academic pursuits.

Let me break this down.

Out of the 7.125 billion people in the world, roughly 6.16 million are academics. That’s roughly 0.8% of the world.

Now, out of that 0.8%, how many do you suppose are in ANY of your overlapping fields? *Gulp*. Now, out of that ridiculously small number, how many do you suppose have gotten around to reading your particular work? *Double gulp.*

I estimate that roughly 8 (eight) people read my master’s thesis from cover to cover. (Did I mention there are 7.125 billion people in the world? ....8.)

I don't know about you, but I don't feel so great.

Don’t get me wrong. This is NOT a post to make you feel like your work is meaningless and worthless and has no point. Far from it. I really, really do believe that academic inquiry is important and valuable. I couldn’t keep at it otherwise.

But I’m not convinced that our work is having the impact that it could have if the academy broadened its definition of what counts as a “contribution” and what constitutes as “filling a gap.” We need to not just focus on filling and finding a gap in terms of content that has been covered, but we need to find creative and innovative ways to fill the gap that exists between academia and the world outside of the ivory tower. This effort to connect with the world outside of academia should be celebrated as a positive contribution.

Some academics like Craig Calhoun at LSE are calling academia out on its focus on specialised publications:

It is a great error for universities to prize publications over scholarship, teaching, and really original research. https://t.co/rsdapTs9hX— Craig Calhoun (@craigjcalhoun) January 1, 2016

Others are trying to re-imagine the dissertation itself:

Sandra den Otter makes the case for reimagining the diss to include publicly engaged scholarship. #FutureHumanities pic.twitter.com/0EjfYatPqX— Josh Lambier (@JoshuaLambier) May 18, 2016

Other conference-like events are bringing together academics and artists and trying to increase public engagement.

Excited to hear Dr. Tim Eatman from @ImaginingAmer speak on "Publicly Engaged Scholarship: The Power of Imagining" #foodinsecurity— K-StateRes&Extension (@KStateResExt) April 4, 2016

In the interest of keeping this post from becoming dissertation-length, I'll cut myself off here. What are your thoughts about this model of academic contributions? Does it gain anything? Lose anything? How do you think publicly-engaged scholarship can be practically achieved? Feel free to comment below or to PM me.

No comments:

Post a Comment